Sampler motifs harken back to the Renaissance when all levels of society satisfied their love of ornamentation with decorative textiles. Professional embroiderers of clothing, bed hangings, and furniture coverings advertised their work and colors to prospective clients on linen cloths. From this came the custom-made samplers for individual use. These were the forerunners of the Pennsylvania Dutch textile samplers. Along with figurative examples, alphabets, one’s name, initials, and dates were added as personalized features. Most were worked in colored silk embroidery on a ground of plain weave bleached linen. From about the 1520s to the end of the eighteenth century, pattern books played an important role in France, England, and Germany, recording pattern designs for use in embroidery, knitting, embroidery on knotted net, and lace making. Some of these designs were incorporated into the European-made samplers that the Pennsylvania Dutch brought with them when they immigrated, and were passed on from generation to generation within family groups, religious communities, and regional areas.

Tandy and Charles Hersh in their 1991 Samplers of the Pennsylvania Germans define a sampler as a “textile used to record and practice embroidery motifs, stitches and alphabets for future use.”[i]

Four periods of development are identified:

- Transition 1683-1776

- Refinement 1777-1809

- Continuity & Change 1810-1860

- Survival 1860-Present [ii]

During these four periods sampler makers positioned the motifs in four different ways:

- randomly without plan;

- in rows according to size;

- uniformly around a centrally aligned figure(s);

- and in mirror-images aligned along a horizontally or vertically positioned central line. [iii]

In southeastern Pennsylvania a teenage Pennsylvania Dutch girl traditionally learned how to make cross-stitch samplers at home using her mother’s, aunt’s, cousin’s, sister’s or other older family members’ sampler(s) as a template. Besides the cross-stitch, the Schwenkfelder [iv] sampler makers are known to have used other techniques as well: double back stitch, geometric satin stitch, and chain stitch. [v]

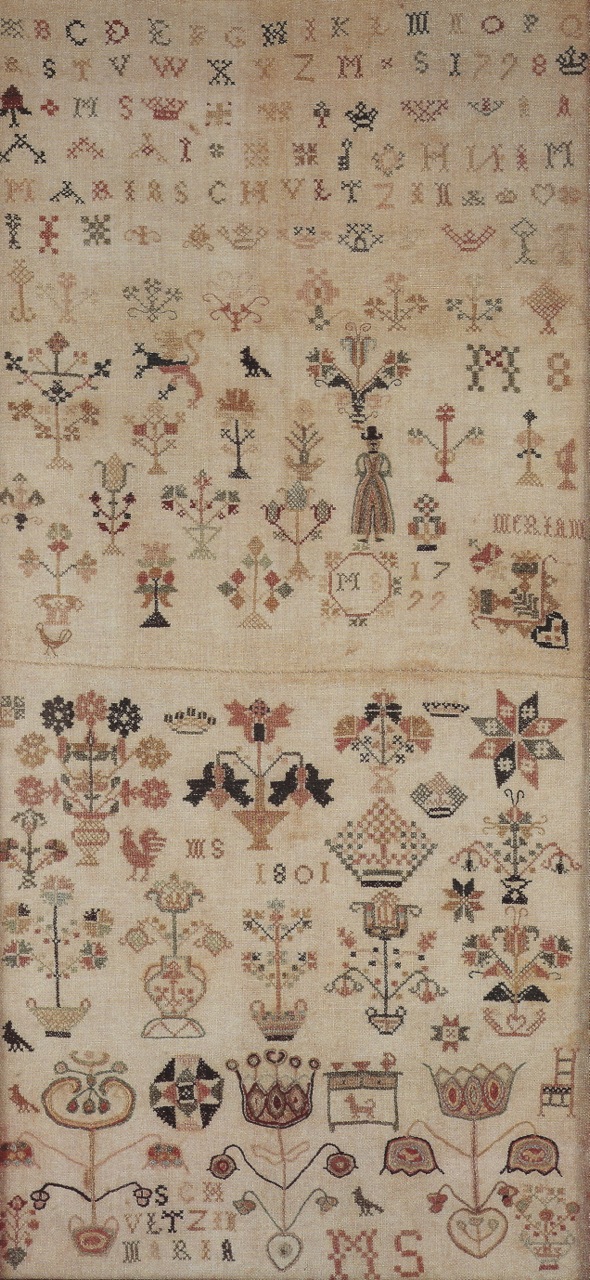

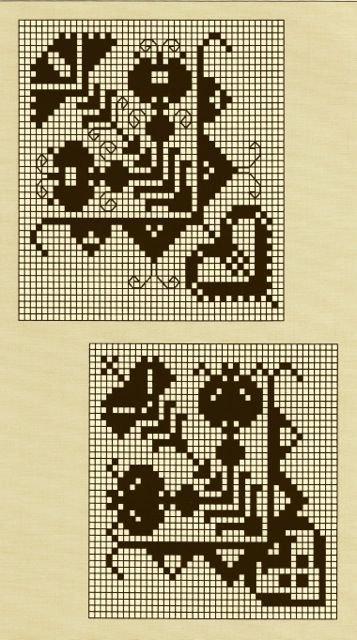

- ILL. 1 . Maria Schultz Double Sampler: 1798-1799 (upper sampler) | 1801 (lower sampler) . Courtesy of the Goschenhoppen Historians in Tandy and Charles Hersh. Samplers of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1991, 137.

Maria Schultz (1785-1841) was a Schwenkfelder, and the sewn together two-piece sampler she made (ILL.1), one with smaller motifs in 1798-1799, and one with larger designs in 1801

was the very first purchase of the Goschenhoppen Folklife Museum, [vi] and the beginning of the present collection [at Green Lane, Pennsylvania]. Its prime importance, beyond its fineness as a piece of early Dutch folk art, is its importance as an evidence of the folk cultural process of acculturation, between traditional groups within the larger Pennsylvania Dutch folk culture.[vii]

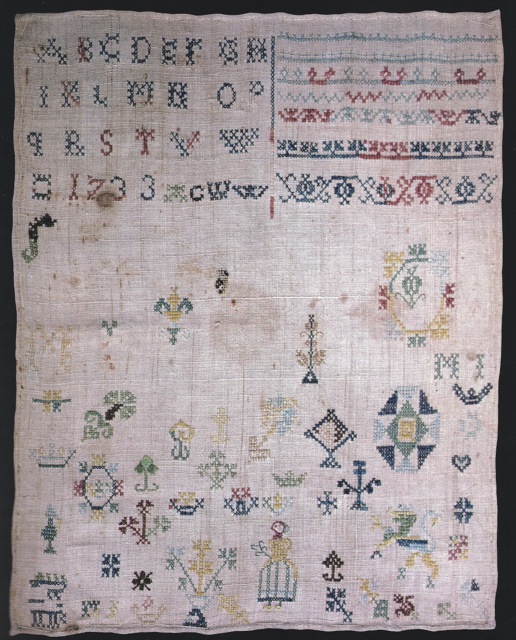

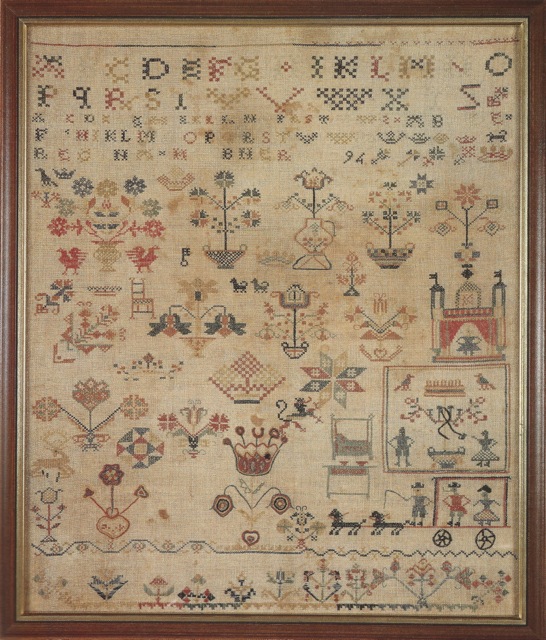

- ILL. 2 . (ACWW) Sampler: 1733. Brought by Schwenkfelder Anna Wagner from Saxony to Montgomery County in 1737. Courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. James Oberholtzer in Tandy and Charles Hersh. Samplers of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1991, 49.

A few of the motifs on Maria’s sampler can be traced back to a random sampler (ILL. 2) Maria’s great grandmother Anna Wagner (ACWW 1733) brought to America from Saxony when she immigrated to Worcester township, Montgomery county (then Philadelphia county) in 1737. Stitches she used include cross-stitch, back stitch, and geometric satin stitch.

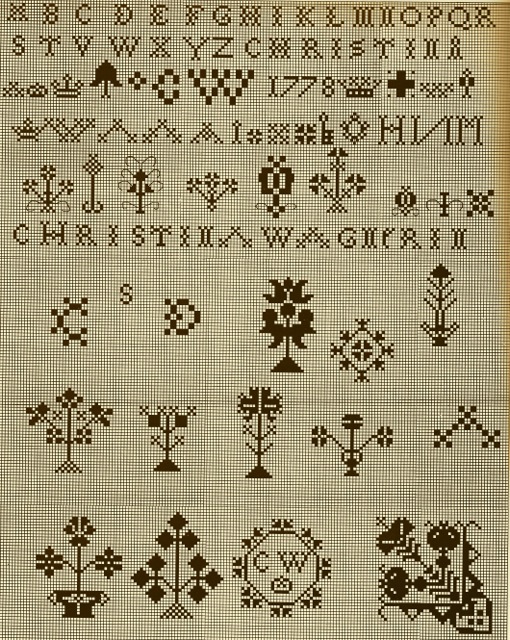

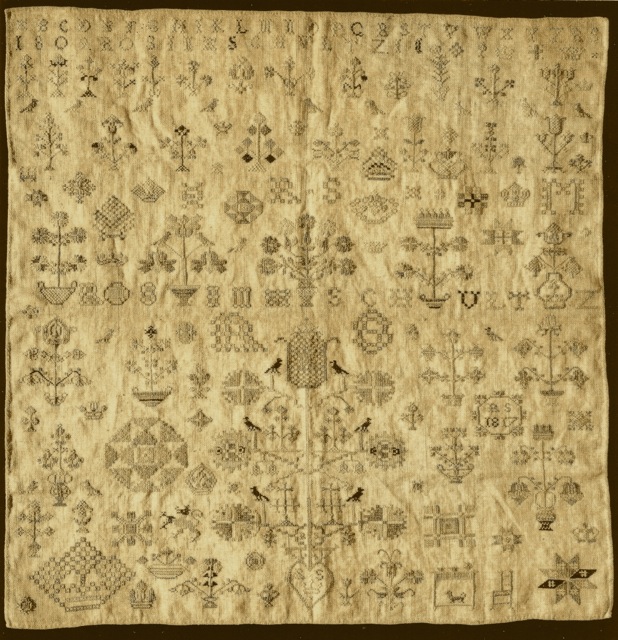

- ILL. 3 . Simulation of Christina Wagner’s Sampler: 1778. Earliest Pennsylvania Sampler of the Schwenkfelders from Tandy and Charles Hersh. Samplers of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1991, 136.

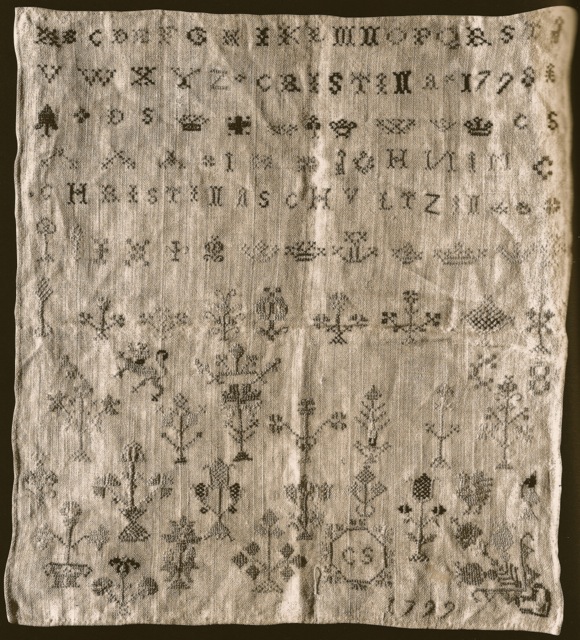

- ILL. 4a . Christina Schultz Sampler: 1798. Courtesy of Schwenkfelder Heritage Center in Tandy and Charles Hersh. Samplers of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1991, 138.

- ILL. 4b . 1801 Christina Schultz Sampler. Courtesy of Schwenkfelder Heritage Center in Tandy and Charles Hersh. Samplers of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1991, 139.

- ILL. 5 . Diagram of Corner Motifs as found (upper example) on a Swiss or German Sampler at the St. Gallen Swiss Textilmuseum, Inv. No. 20046, and (bottom example) on Christina Wagner’s, two nieces Maria and Christina Schultz’s and her cousin Regina Hübner’s samplers in Tandy and Charles Hersh. Samplers of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1991, 115.

In 1778 Christina Wagner, Maria’s aunt, and Anna’s granddaughter created a rowed sampler (ILL. 3) , copying six of the thirty-one motifs from her grandmother’s sampler. Maria and her two sisters Christina and Rosina, also residents of Worcester Township, used their aunt’s sampler as a guide. Maria was thirteen, and Christina sixteen when each made her first sampler in 1798-1799: Christina chose a row format (ILL. 4a) like her aunt’s, whereas Maria placed her figures randomly on the canvas (ILL. 1, Top). However, both copied many of her motifs, including the small designs and letters in rows three to five and the bottom row with a cartouche enclosing their initials. Most notable of all is the corner decorative figure that can also be found on a Swiss or German sampler housed at the Textilmuseum in St. Gallen, Switzerland Inv. No. 20046, and scarcely changed in Christina Wagner’s nor subsequently in her nieces’ and other Schwenkfelder samplers (See illustrations in this post: Christina Wagner: ILL. 3; Maria Schultz: ILL. 1, upper sampler; Christina Schultz: ILL. 4a ).

- ILL. 6 . Regina Hübner Sampler: 1794. Courtesy of Schwenkfelder Heritage Center in Tandy and Charles Hersh. Samplers of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1991, 55.

Melchior and Salome (née Wagner) Schultz, Maria, Christina, and Rosina Schultz’s mother and father, took Regina Hübner into their home after her parents died. Her two younger cousins borrowed freely from the random sampler (ILL. 6) Regina had made in 1794 at age seventeen : three carnations; a crown with three diamonds; the seven flowers and vase; three tulips in a vase; five cross flowers; rooster, small corner flower, large corner flower, a chair, a table with two bowls, along with a creative addition of a cruet, and dog standing on the lower table shelf. Stitches they used include cross stitch, double back stitch and chain stitch (See illustrations in this post: Regina Hübner: ILL. 6; Maria Schultz: ILL. 1, lower sampler; Christina Schultz: ILL. 4b; Rosina Schultz: ILL. 7).

- ILL. 7 . Rosina Schultz Sampler: 1809. Courtesy of Schwenkfelder Heritage Center in Tandy and Charles Hersh. Samplers of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1991, 119.

In 1809 Rosina, the youngest girl of the Schultz family, made a random sampler (ILL. 7) of over one-hundred motifs, many of which replicated her sisters’ designs, and which carried the sampler tradition into the next generation, serving as a template for her three daughters, Salome, Maria and Rosina Kriebel. Sara Schultz, daughter of Rev. Christopher and Susanna

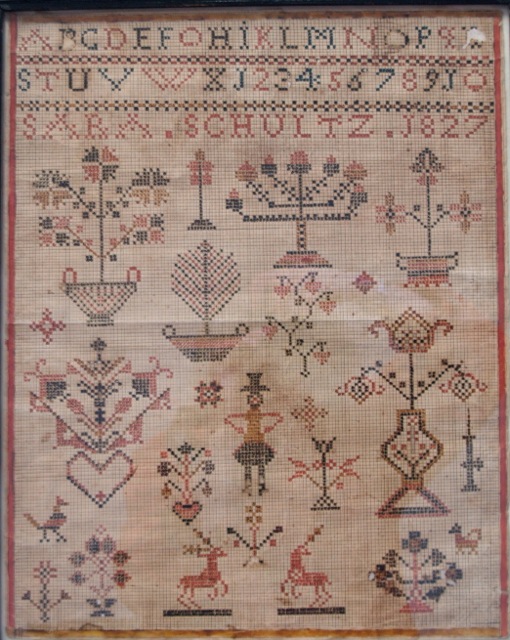

- ILL. 8 . Sara Schultz Sampler on hand-drawn lined paper: 1827. Courtesy of Reading Public Museum. Photo image © Del-Louise Moyer.

Yeakle Schultz, a peer and cousin to the Kriebel girls, did not make her home in Worcester township, Montgomery county like most of her Schultz relatives, but rather lived in Berks county. Here she created a random sampler (ILL. 8) on paper at age seventeen in which she combined six of her mother’s sampler motifs with ones from her Aunt Christina Wagner. She also added designs from her other Schultz kin of Worcester Township, along with those in the northeast Berks Franconia Mennonite Area. [viii] Such borrowed designs, also known as signature motifs, inspired other Schwenkfelder sampler makers, who repeatedly and faithfully borrowed the very same images, sometimes creating variants thereof, in cross-, back-, and chain stitches from ca. 1809 to 1875.

The Schwenkfelder tendency to borrow, replicate, and create alphabets and variant designs in their textile samplers is repeated in their illuminated manuscripts on paper as well, the ABCs and visual motifs being common to both mediums. Printed writing samples such as J. J. Brunner’s 1767 Vorschrift zu nützlicher Nachahmung…[ix] or A Useful Writing Sample for Copying… were available to the general public, and demonstrated several variants of the same Alphabet. Schoolmasters used such works as references when creating writing samples for their students. These same alphabet variants appear in textile samplers, and change according to regional cultural influences and time period. The Schwenkfelder samplers exclusively used the alphabet that appears on the sampler (ILL. 2) that Anna Wagner brought with her to Pennsylvania in 1737 right up to1875 when Regina Schultz used it in her first sampler. [x]

A school teacher before becoming a minister, David Kriebel (1787-1849), one of the best known of the Schwenkfelder frakturists, made a writing sampler or Vorschrift „Jerusalem Du Gottes Stadt or Jerusalem You City of God [xi] for Abraham Anders on February 24, 1805. Like Brunner, Kriebel intentionally demonstrated several ways to present the same letter(s) in Fraktur script for his pupil to imitate. Abraham would build upon this, and eventually use his quill, like the Schwenkfelder young ladies used their needles, to create a new design variant.

Susanna Hübner (1750-1818), another renowned Schwenkfelder frakturist, lived with her brother Abraham (also a frakturist) and his family on the old homestead after their father’s death, and made illuminated manuscripts for all of the children. She found David Kriebel’s illuminated initial “J” of “Jerusalem” from the Anders Vorschrift so appealing that she devised a near replica of it as the initial letter “J” for her nephew Jacob’s Christian name in an illuminated manuscript Jacob Aber Zog Seinen Weg or Jacob Went His Own Way (Genesis 32: 1-2) that she created for him on April 2, 1808.

We find the same tendency in Schwenkfelder frakturist families as we do among the Schwenkfelder textile sampler maker families. Close proximity encouraged relatives to borrow each others’ designs and ideas, but in a creative manner. Susanna Hübner made her niece Maria an illuminated manuscript to the text Maria Hat Das Gute Theil Erwählet. Das soll nicht von ihr genommen werden… or Maria Has Made the Right Choice. That Should Not Be Taken From Her… (St. Luke 10:42) on December 4, 1808.

Maria faithfully copied a portion of her Aunt Susanna’s gift Maria Hat Das Gute Theil Erwählet. Das soll nicht..,.using the same color scheme for the text, and the same vase of tulips. However, in the process she respositioned both, and added a bird perched on a very original elongated flowering tree, thus creating an entirely new variant based on her Aunt’s original.

On December 16, 1804 David Kriebel made special gift for Susanna Kriebel surrounding the text Gott hat in meinen Tagen mich väterlich getragen or During my Life God Has Supported Me in a Fatherly Way [xii] with floral designs reminiscent, in the opinion of some, of central and eastern Europe. Dennis K. Moyer in Fraktur Writings and Folk Art Drawings of the Schwenkfelder Library Collection found that “the color and motifs that he chose seem to imitate a quality and style similar to the art and textiles of the Near East. Perhaps the ideas for the design and color were drawn from printed or woven textiles.” [xiii]

The similarities between the vertically-oriented drawing (bookplate?) Susanna Hübner made for her niece Susanna and the rectangularly conceived religious text framed in a dense floral border that David Kriebel created for Susanna Kriebel are obvious. Hübner borrows profusely from Kriebel, but lightens up the density of his flower-patterned periphery by adding mustard yellow to the darker blue and red colors, as well as by interspersing feather-like leaves among the floral foliage. Her multi-rayed star is more vibrant and takes on a three-dimensional energy because of the circular background rays. A brilliant addition is the potted floral bouquet that Aunt Susanna places in the center of the picture above her niece’s name. It is so geometrically conceived that it could easily be included in a textile sampler.

In 1818, Maria Hübner rethought the drawing her Aunt Susanna had made for her sister, deleting the name, but keeping the motifs almost exactly intact. She chose a more subdued

pastel palette of colors , and added two flowering vine plants, one above the other on the right-side margin of the leaf. The drawing is a tribute to her Schwenkfelder heritage, a reconceived amalgam of friends’ and family’s designs in a color scheme of her generation.

Whether the medium was textile or paper, the Schwenkfelder artists, with needle and quill, were imitating and transforming designs and alphabets from what they had available in their time and place. By recycling these visual motifs and texts, they extended the cultural life of their community for generations to come. In the eighteenth century one expected to find the Pennsylvania Dutch girl’s sampler in her sewing basket, ever ready with the designs she could choose for her sewing and embroidery needs. As time progressed, the purpose of the sampler changed, and became more ornamental than practical. What used to be tucked away, was now framed and hung on the wall. The same is true of illuminated manuscripts that originally were kept away from view taped to the lid of one’s dower chest, and/or safely put away in a drawer or folio Bible. Labeling them folk art, and promoting their commercial potential as decorative wall accents has replaced their cultural value as the Pennsylvania Dutchman’s private expression of his love of God articulated through art.

ENDNOTES

[i] Tandy and Charles Hersh,. Samplers of the Pennsylvania Germans. Birdsboro, PA: Pennsylvania German Society, vol. XXV, 1991, 14.

[ii] Ibid, 47.

[iii] Ibid, 14.

[iv] The Schwenkfelders, followers of Kaspar Schwenkfeld von Ossig (1490-1561), were severely persecuted for their non-orthodox beliefs. Fleeing in 1726 from oppression in Silesia , they were first welcomed by Count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf on his estate at Berthelsdorf and Herrnhut in Saxony. This proved to be a temporary home. From 1731 to 1737 small bands emigrated to Pennsylvania where they settled in the Goschenhoppen, and Skippack areas among the Mennonites, Lutherans, and Reformed who had also settled in this part of Montgomery county (then Philadelphia county) around the same time. All of these settlers transferred a bit of their cultural heritage to southeastern Pennsylvania, some of which can be said to be common to all, and some of which can be recognized as unique to one group or the other.

[v] Dorothy D. McCoach. n. d. Conservation Report for Maria Schultz Sampler 1798, 1799, 1801 (Project #: 01.103.A), n.p., pp. 1,2.

[vi] The Goschenhoppen Historians, Inc., presently celebrating the 50th anniversary of their incorporation, continue to identify, preserve, and disseminate the Pennsylvania German folk culture and history of the Goschenhoppen region.

[vii] Isaac Clarence Kulp, Jr., ed., “The Cover Picture,” The Goschenhoppen Region vol. 1, no. 1 ( Peterkett/St. Peter in Chains Day August 1, 1968): 2.

[viii] Hersh, 145.

[ix] Johann Jacob Brunner. Vorschrift zu nützlicher Nachahmung und einer fleissigen Übung zu Gutem vorgestellt und geschrieben durch Joh. Jacob Brunner älter von Basel. Gegraben in Bern von Carl Gottlieb Guttenberger aus Nürnberg. Bern, Switzerland: n.p., ca. 1766.

[x] Hersh, 67.

[xi] Jerusalem Du Gottes Stadt gedenke jener Plagen….in Das kleine Davidische Psalterspiel. Germantown: Christoph Sauer, 1744, p. 216, Hymn 221, verse 1.

[xii] Gott hat in meinen Tagen mich väterlich getragen….is part of the opening line of a seven-verse religious poem by Jakob Friedrich Feddersen (1736-1788).

[xiii] Dennis K. Moyer. Fraktur Writings and Folk Art Drawings of the Schwenkfelder Library Collection. King of Prussia, PA: Pennsylvania German Society, vol. XXXI, 1997, 115.

My thanks to Bob Wood, and Linda Szapacs of the Goschenhoppen Historians; Dorothy McCoach, Independent Conservator; Dave Luz, Hunt Schenkel and Candace Perry of the Schwenkfelder Library & Heritage Center.

Schwenkfelder Eighteenth & Nineteenth Century Textile Samplers and Writing Samples Blog Post including transcriptions; translations; and photo images excepting illustrations in Tandy and Charles Hersh’s Samplers of the Pennsylvania Germans © 2016 Del-Louise Moyer

What a fantastic collection.

LikeLike

Both the Goschenhoppen Historians, and the Schwenkfelder Library & Heritage Center have very special collections that represent the past in the upper Perkiomen Valley in Montgomery county. We’re all so fortunate that there are people at both, who are helpful and anxious to share these treasures!

LikeLike

Del,

What an attractive and informative summary of the sampler collections! Thanks you for collecting the images and for your usual interesting and informative research and commentary.

Bob

LikeLike

Lovely! Thank you for including me in your list. Am now forwarding this to a retired colleague who does cross stitch. I tried it but usually did back stitch as a youngster.

LikeLike

Beautiful pieces, well photographed with terrific background information! Thanks again, Del

LikeLike

Very nice article, Del! Thanks!

LikeLike

To me, the most interesting aspect of your writing was the idea that samplers were used for reference, instruction and inspiration long before they were wall decorations. (Modern type designers, take note!)

Anyway, I learned something new today and it’s not even 10am. (Thanks, Del, for your work and your sharings!)

LikeLike

Thank you Del. I’m fascinated by the work of the frakturists, having been introduced to this art form when visiting the Goschenhoppen Festival two years ago.

LikeLike